Our 100 Words…

Alison

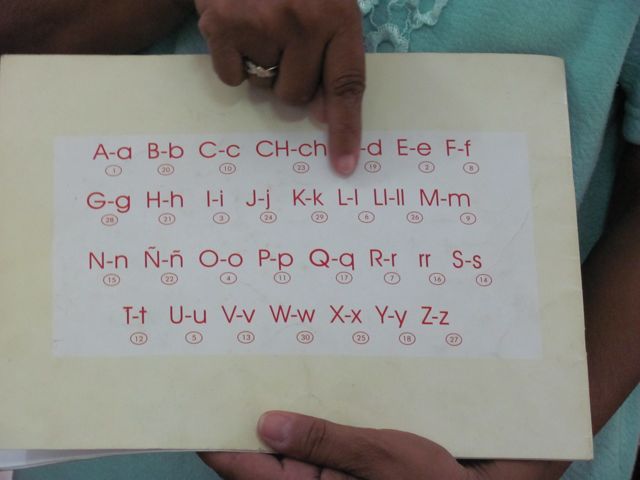

In 1960 Fidel Castro addressed the United Nations and boldly announced his plans to “eradicate illiteracy within six months.” By November 1961, Cuba’s National Literacy Campaign, having sent young and old into adjoining neighborhoods and remote villages, was in full swing. A brilliant strategy that now allows Cuba to claim a 98-99% literacy rate. However, as I consider the following emotional recollection of our 68 year old tour bus driver, I believe the brilliance of this campaign was also in its ability to unify Cubans, promote national pride, and encourage solidarity at a time when the success of the revolution depended on a committed citizenry:

“There are events that transform us as humans…I have had three such

events in my life. One was when I became a father, one was when I

worked in Africa and one was serving as a ‘soldier in Castro’s national

literacy campaign’ (Nafal, 5-18-10).”

Megan

Cuba: A Lesson In Contrasts

Decaying buildings teeming with life

Hot, tight classrooms exuding youthful energy

Many voices with one common message

Ancient autos driven by sixteen year old boys

Hot rice and beans served with cold mojitos

Ration centers nestled next to luxury hotels

CUCs and pesos: two prices, two systems—side-by-side

Proud heroes who are also feared enemies

Hopeful people focused on forgotten causes

Meeting basic needs while beggars still walk the streets

Accordion buses bursting with workers lumbering by tourist buses barely filled

Shared solidarity, but individual lives

Personal aspirations within government control

Arriving in search of answers, but leaving with even more questions

Bill

The revolutionary project lives; neither history nor Fidel, informing everything I have learned here.

The Literacy Campaign changed women. Young, old acknowledge women liberated from homemaking and the people from illiteracy. We met many women community leaders, activists, professionals- important, volunteering, and driving the continuing project.

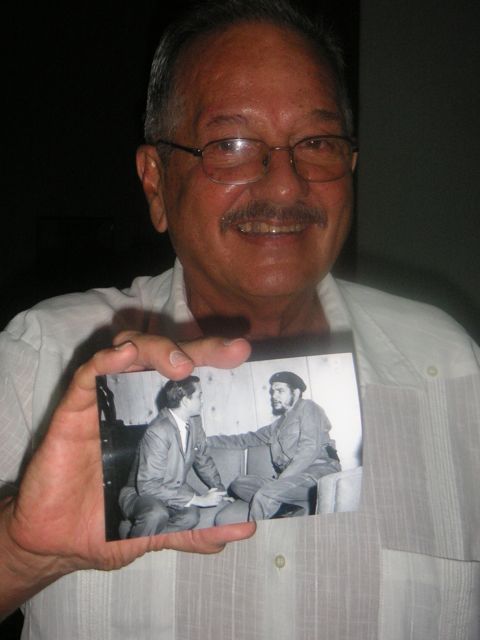

Stoic Nefal teared-up recalling his Literacy Campaign experiences. Yepe—teen underground revolutionary, friend of Che, protocolist, ambassador. Warm, welcoming, clear. I will write him as this kind of access is so seldom found. He embodies the project.

Cynicism, euphoria, that is the continuing project—recognizing and responding to both. It’s all for the people.

Jim

100 Words for Pork

- Roasted

- Grilled

- Shredded

- Old clothes

- Secret sauce

- Dry

- In soup

- Smoked

- Regurgitated

10. Sliced

11. Gordon bleu

12. Pounded

13. Uruguayan

14. Chunked

15. Brochette

16. Pork chop

17. Suprema

18. Cerdo

19. Ham

20. Wurst

21. Sausage

22. Ham on ham

23. With cheese

24. Cuban sandwich

25. On pizza

26. Chorizo

27. Steam tray pork

28. Fuster pork

29. Lactating pork

30. Pork wontons

31. A side of pork with a pork meal

32. Roasted pork loin

33. More pork?

Heather

Cuba is a country that explodes in color. The flowers and trees have a vivid range of color, as exemplified by the hibiscus, the national flower. The cars, of course, come in every color imaginable, and some never imagined by the original manufacturers. Artists in Cuba capture the brightest colors in their work, and the many of the buildings are brightly painted. Even the people come in a range of colors—from reasonably pale (though one person stopped one of us to say, “You are the whitest person I have ever seen”), to very dark. In terms of color, there is not a Cuban standard look.

While much of the color seems quite haphazard, some is quite ordered. The school children throughout the country, for example, all wear a uniform in the appropriate color for their age. Red with a blue scarf for the youngest, red with red for the older, gold for the high school students, and various shades based on the field for the college students. Blue for the police, and green for the military. Bright yellow spotted ties for the taxi drivers. Black and white for the food service people. You can identify many people at a glance by the color of their clothing.

Even the license plates on the cars are color-coded. Yellow plates are for private cars, blue for state owned, red for rentals (with a plate beginning with “T” for the tourists), white for upper level state officials, orange for foreign workers, and black for the military. All neatly ordered, on the surface.

Joan

FERNANDO * “Would you like to see the most beautiful church in Havana?” * PHOTOGRAPHY * Agua con gas * CUC * Butter rum lifesavers * ENSALADE * Coco Taxi (3x) * PLAYGROUNDS? * Hotel Habana Libre * BARBARA * Mas café por favor * LOGOPEDIA * French fries * ESCUELA * Wooster 9 * IGLESIA * Espresso cups of sweetened coffee * VEGETARIANO * AA batteries * CUCUMBERS * Black Beans * RICE * Taxi? No gracias * Rash girl * Mojito? No gracias * “Lady, open your bag.” * Quanto cuesta? * Muy cocidas * HUEVOS * “Hello lady!” * SPAGHETTI * Beth’s notebooks * PIZZA * Habla Ingles? * PINEAPPLE * Ice cream with fruit * NAFAL * “You are very white.” * RITA * TATIANNA * Literacy museum * FRIENDLY * The man in the pink shirt * José Marti * CCTV in English * HOT * HUMID * Change your batteries * CATS * DOGS * Switchy doll * SILENCIO * “You like my country?” * BENADRYL * “We share what we have.” * HOUSING * “There are things that transform you as a human being.” * SOLIDARITY * REVOLUTION * AA batteries * BLOCKADE *

Beth

Things I learned in Cuba:

• The Palm Tree, though not indigenous, is the national tree of Cuba.

• Private, collective and state farms exist; private farms yield more produce in general and the produce is more diverse.

• The first railroad of the Americas was built in Cuba in the 1830s.

• Cuba’s national hero is José Martí, a poet, an essayist, an activist. He is quoted everywhere and his bust is to be found EVERYWHERE. After a visit to Cuba, if you do not know Martí, you have not seen Cuba.

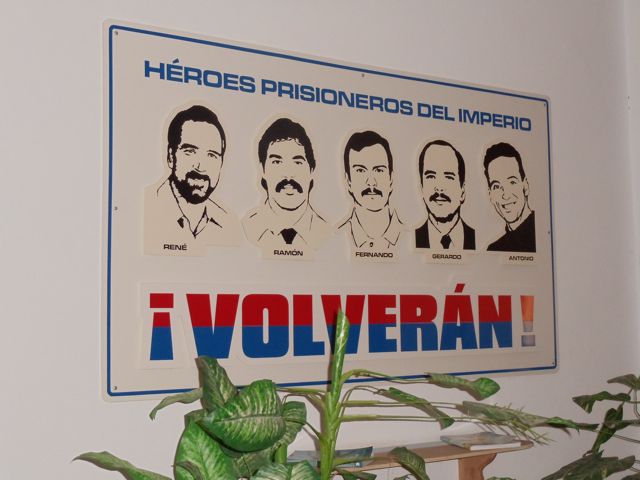

• Next to Martí, the three most commonly found heros respresented on posters and signs are Che Guevera, Mella, Camillo Cien Fuegos.

• The only advertising you see is in defense of the revolution (todo por la revolution).

• Images of Rual and Fidel Castro are not found, according to Fidel’s anti-cult of personality.

• You can hear roosters crow every morning from the 20th floor of the Habana Libre Hotel (formerly the Cuban Hilton).

• You cannot wander freely as a visitor on the University of Havana campus.

• Fernando Ortiz, a sociologist, came up with the idea of transculturation, in which we adopt aspects of foreign cultures we encounter into our own (colonialism isn’t a one-way street).

• We have decided to adopt Mojitos, the collective, and rumba into Wooster faculty meetings.

• Cuban cigars are very smooth. The rum is too. Coffee too. Coffee and rum even better.

• “There is no sugar cane production.” The Ministry of Sugar is just down the street from our hotel.

• “There is no poverty and the aging population is given great attention.”

• Of the few beggars we saw in Old Havana, most were elderly folks.

• The concept of becoming a medical doctor in order to earn a high salary is completely foreign.

• Goats can be found grazing on the former military airport grounds and run-way.

• Cubans walk and hitchhike on the highway.

• You can flag down any vehicle with government plates and ask for a ride.

• Former military barracks and grounds have been converted to primary schools (true to Fidel’s mandate).

• All Cubans have a ration card to get their groceries, so they are never without the basics.

• You must love rice, black beans and pork to survive here.

• The symbol of the Federation of Cuban Woman is a woman holding a machine gun.

• Illegal drug use stems from different substances “washed up on Cuban shores from passing boats.”

• The number one problem facing Cuba (aside from issues of the blockade), is housing.

• We can all do a mean rumba when encouraged properly, out of the public eye, and on top of a rooftop in Old Havana (i.e. location is everything).

Matthew

What stands out for me as we leave Cuba are the purposeful steps towards progressive educational practices that appear to be country-wide. Though I am not a huge fan of the standardized educational movement (even in the U.S.), I am amazed at the Cubans’ efforts to provide quality instruction regardless of location. One example of this practice is their use of a low-tech “distance learning” methodologies via T.V. and VCR. Across the country, students are exposed to the same researched and vetted teaching strategies; from inner city Havana to distant rural villages, the quality of the instruction is not just consistent, but the same. While this method may not be fostering the 21st Century skills we hold so dear in the U.S., it does make the Cuban people poised and ready for when more technologically advanced modes of distance learning become available. The process is in place; they are just waiting on the technology to help take them further.

Day 7

Day seven and we actually leave Havana. We are scheduled to visit a rural community that is approximately an hour and a half drive north of the city. Along the four-lane, well-maintained road is a lush and what appears to be fertile land. Filtering through an eastern and southern African perspective, I am struck by the number of tractors (albeit old but definitely working) and cement houses with electricity. Less developed certainly covers a wide variation of living standards and electricity for Ethiopian farmers is only for the privileged few. Certainly this country has progressed far beyond the reliance of subsistence agriculture.

We arrive at La Terrazas (or the Terraces) and are greeted by our guide for the day. Cuba Libres are our welcome drink and it is always nice to have a mixed drink before noon. We are introduced to what is being called a Biosphere. While there is always the english/spanish translation issue I think of a Biosphere more as a self-contained ecologically balanced environment. This is more of a small community that relies on tourists wishing to see something outside Havana. The area was a former coffee plantations settled by French fleeing the Haitian revolution of the late eighteenth century. The coffee farming proved unsuccessful, partially due to soil erosion off the hillsides, and by 1850 or so most of the French had left. While farmers lived in the area, the current government undertook a significant environmental and community planning project that began in the early 1970’s. The housing is multifamily cement centered around two smallish ponds. The buildings fan out and up the gentle hills and are all relatively well maintained. The population consists of approximately one thousand inhabitants with the majority of the adults involved in the tourist services provided here. There is an agricultural research station but we are not shown the facility and cannot see it from the road. We spend the day visiting a school, the former coffee plantation, having lunch and swimming in a small river. Alison impresses all of us with her reckless abandon as she dives off some rocks into the swimming hole. The early evening ends with a sleepy ride back to the capital.

Of interest to me during the day were some discussions centered upon daily life in Cuba and the renaming of the school that we visited. The school had been called “the fifth of May” but was now called “school of the Eastern Republic of Uruguay.” While the fifth of May is Karl Marx’s birthday the latter reflects sponsorship of the school brought about during what is referred to as Cuba’s “special period.” This period, which begins in approximately 1993, reflects the end of beneficial trade agreements with the Soviet Union and a resulting 35% decline of GDP. The country responded in many different ways ranging from issuing one million bicycles to Havana’s residents because of the fuel shortages (these currently sit unused as the country has reverted back to bus and car transportation) to sponsorship of local school by other country’s governments (hence the Uruguay name). This special period also raises the broader issue of the economic struggles Cuba has experienced and their relatively pragmatic responses. The U.S. trade embargo, the collapse of the Soviet Union and the current realization that tourism can bring much needed revenue are all challenges that the government has handled relatively well. While it is unclear about the true popular support for the government this does not appear to be a country seething in frustration for a change in leadership (ie, Moi’s Kenya or the current situation in Ethiopia). The current phase of embracing tourism, begun in the mid-nineties, seems like another interesting response to the realities of their international trade (people are quick to point out that sugar cane is no longer a primary export). In order to facilitate tourism, while being relatively consistent with some socialist ideals, Cuba has set up two economies. The country’s use of multiple currencies is both odd from a socialist perspective but also fairly effective from an economic one.

I have a pet theory that socialists don’t handle financial relationships well. Marx spoke at great length about production and proletariats but he was relatively less clear about financial issues. My take is that socialists set exchange rates and forget about them for decades. However, if you think about it the exchange rate is the ultimate price for everything in the country (at least from a foreigner perspective). Cuba has a problem with this because the pricing mechanism is heavily manipulated for social purposes. One of the more stunning examples is the inability of residents to sell their houses. If they want to move they literally have to find someone to trade with. Of course, the typical Cuban receives a monthly ration of general food supplies and a small monthly wage to augment these purchases. Allowing tourists to enter this heavily subsidized pricing world could create potential havoc with resources. In response to this dilemma, the government has created a two-tiered currency system that includes local pesos for Cubans and convertible pesos for tourists and wealthier locals.

Upon entering the country we are instructed to exchange our currency into Cuba convertible pesos. They are referred to as CUC (pronounced kook) and represent the currency for use by tourists and wealthier Cubans. The rate is approximately .8 CUC to the Canadian dollar and U.S. dollars are purchased at a 10% penalty. Local pesos can be purchased at 25 pesos per CUC. Essentially what has occurred is a parallel tourist economy based on CUCs. The heavy government regulations and lack of many desirable products prevents the two worlds from interacting much. Although, I did managed to pay in CUCs for some heart medication I forgot that was actually priced in pesos. In other words, I paid 25 times more than the actual price for my medication.

Overall, this seems to be a fairly effective for taxing richer tourists while, at the same time, maintaining the distribution structure for the typical Cuban. Overall, the country has three levels of economic allocation. Essentially basic foodstuffs are rationed to Cubans on a monthly basis (sugar, rice, oil etc.), there is a salary in pesos for other relatively basic items and there are the CUCs. For the majority of Cubans goods and services are provided without charge or heavily subsidized. All of this means that only the prices for luxury items (fancy dinners and other touristy knick knacks) resemble more international market prices. From a U.S. perspective, an interesting economic pedagogical issue becomes how one speaks to allocation when price is not the primary method of distribution.

We joke that supply and demand is the central component of all economics classes. However, I wonder how economics is actually taught here. Does it rail against the unfettered market and suggest the need for significant government intervention or is it mostly taught from a Marxian labor theory of value perspective? If it is the latter, how come I have so many CUCs in my pocket?

Day 6

“Hello United States! Remember me?” (the man in the pink shirt)

Our morning was spent visiting the Latin American School of Medicine (ELAM), a 20-minute bus ride from our hotel. There, we were met by the Director of the Foreign Affairs department who led us to a large conference table, complete with tabletop microphones (did I mention that the table was large?). Given the rain pounding the roof, these were a welcome addition. This facility was opened in response to a need for doctors who could assist victims of natural disasters. At the time that Fidel was searching for a location for this new school, Raul was the president of the armed forces. Raul felt that they needed three months to convert this former military academy, but Fidel gave them one month to empty and renovate the school. The school was inaugurated 11 November 1999, with 1,534 students from 18 countries enrolled. There are 300-350 faculty members.

Although the students are not selected by Cuba, there are several requirements that students must meet: (1) 18-25 years of age, (2) high school graduate (college graduate if from United States), (3) no health impairment or addiction, and (4) underprivileged students or those from families without the resources to pursue medical education. In 10 years, they have graduated more than 7,200 physicians (34 from the US).

The program runs 6+ years. For students who are not fluent in Spanish, they begin with six months to one year of premedical school to study the language. The first two years in the classroom focus on basic sciences, followed by clinical rotations.

Most students complete the entire program in Cuba. However, some return to their home countries for their 5th and 6th years. This enables students to gain experience with conditions that are present in their home countries but not here. An example used by the director was treating gunshot wounds; they don’t sell weapons in Cuba so students are not exposed to these injuries during their training.

When leaving the facility, we ran into two students from Boston and New York. When asked why they chose to pursue medical school in Cuba, the response was twofold: “It’s a free medical education” and “They really teach you how to be a community doctor.” The students pay no tuition and all books, uniforms, housing, and meals are provided. In addition, students are provided with a monthly stipend.

This program is funded by the Ministry of Health in Cuba. Our guide did not have an exact figure but guessed that the cost was ~46,000/student. We asked if these doctors-in-training were helping to fill an unmet need for medical care in Cuba but this was not the case. Rather, it seems to be an effort to export human resources where they are needed in the world. At present, there are 428 graduates of this program (6 from the US) in Haiti.

In other news, the Wooster 9 came close to becoming the Wooster 7 yesterday afternoon, while capturing the train photo. Fortunately, our 7 colleagues noticed our absence and had them stop the bus.

Mission: Literacy

Day Five – Mission Literacy

Little did we know that the road leading into the Museo Nacional de la Campana de Alfabetizacion would be so illustrative of the Cuban literacy movement. We turned into the former Batista military barracks, a sprawling compound of spartan, symmetrically placed buildings, and were met with over a half-mile of streets lined with Cuban students dressed in their national uniforms. Our guide informed us that this military grounds was the home of Batista’s army and was the location of the airstrip from which Batista fled as Castro advanced on Havana. After Castro assumed control, he pledged that the military installations would be turned into schools for the children of Cuba, and 50 years later, the children of Cuba are still reporting daily to participate in the process of becoming an educated Cuban – a process that began with military precision as an all out war on illiteracy.

This process of educating the people of Cuba is most famously told through the National Literacy Campaign started by Castro in an attempt to bring the entire Cuban population up to a first-grade reading level. To accomplish this, he called upon 105,000 youth aged 8-17 to be trained and then flood the countryside to provide individual, one-to-one literacy instruction to everyone in Cuba that could not read or write. In less than a year, Castro’s goal had been met – a truly impressive feat.

Our own tour bus driver was one of the youth who, at the age of 16, ventured into the rural villages in order to teach his fellow Cubans. When describing this experience to us he was so overcome with emotion that it became hard for him to continue. His reaction highlighted a much deeper political purpose for the National Literacy Campaign. We were not just talking about a need to have an educated populace – this campaign created an understanding for how all Cubans lived. It ingrained the importance of taking care of the Cuban community as a whole. Teaching reading was a way to build empathy, a way to connect rural and urban populations that had very little contact or understanding of each other, and promoted a deep cultural ethic for learning.

While the campaign is well behind us, the impact of this ethic has far-reaching impacts, one of which was highlighted in our second meeting today. We spent time meeting with the Comprehensive Workshop for the Reconstruction of the Neighborhood. After listening to the group’s process for researching, identifying, and developing solutions for community-based issues, Jim gave us the perspective that typical community development programs in developing countries can be limited because the community-based participants can lack the advanced education needed to implement and monitor their programs on the ground. The leaders of the Comprehensive Workshop were all highly educated and well versed in not just the needs of the community, but the solutions that will work within the community’s context. They had the knowledge and skills needed to identify, articulate, and monitor the needs of the community – a very powerful combination.

On the food front, today was a very porky day. We had two unique meals in very different locations, both featuring substantial quantities of pork (our dinner was translated as “old clothes”). We (Matthew, Jim, and Bill) actually ordered (we insist it was a miscommunication with the waiter) a side dish of just meat to further immerse into the Cuban experience. For those keeping score at home, that was an entrée of meat with a side of meat. Perhaps we will try some veggies tomorrow.

Matthew

Day 4

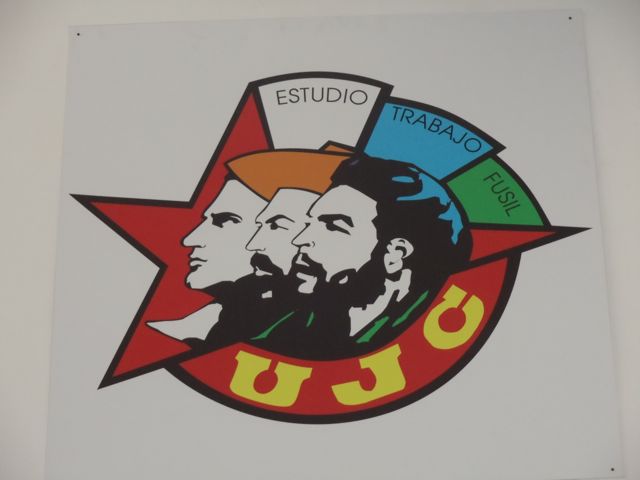

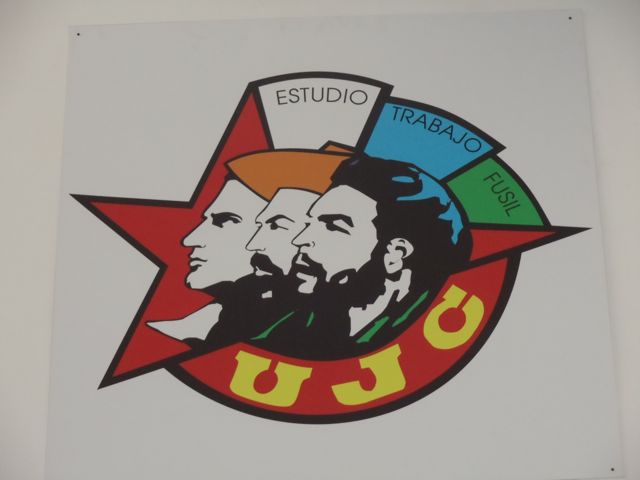

Estudio, Trabajo, y Fusil

Study, Work and Defend! This slogan, noted on a sign upon our entrance into the National Trade Union Center of Cuba, set the tone for our travel and study today. A day filled with the examination and discussion of the Cuban educational system, the rights of the worker (specifically related to the field of Education), and the role schools play in fostering a national identity (including a clear understanding of Cuban history and common cultural values). A thread running throughout all our visits today (and throughout this trip) seems to be the concept of “transformation”—and the recognition that systems in Cuba are constantly being transformed.

TRABAJO…Our day began with a meeting with Diosdada Vidal Valle, a very informative and passionate representative of the Asociacion Cubana de Pedagosos (Association of Cuban Educators), a trade union focused specifically on the interests of trade workers in Education, Science and Sports. This trade union represents a grassroots, bottom-up effort to represent and defend the rights of the workers. The conversation focused on the structural organization of schools at the municipal, provincial, and national level. Union membership includes teachers, administrators, members of the Ministry of Higher Education, trade workers manufacturing educational materials, and members of the scientific research community. While it is not compulsory to belong to the union, 97% of all potential workers do and pay dues of one percent of their annual salary. In many ways, the model of this union mirrors those of educational union systems in the United States in both structure and purpose—varying primarily by categories of membership—specifically noting that school administrators and members of higher education institutions are not part of the U.S. system.

The structure of Cuba’s educational system was also of interest to the group. Children attend primary (grades 1-6) and then secondary school (grades 7-9). At the culmination of the ninth grade students face an educational fork in the road where they take a series of required exams and are asked (or advised) to identify a career-path leading either to pre-university studies or technical studies/training. Interestingly, the number of spaces available at the pre-university level is based upon the needs of the State. Valle noted that as more trade technicians are needed in some municipalities, fewer pre-university spaces are available and the requirements for entrance into these programs is more competitive, thus redirecting many students into technical tracts. This caused many in the group to wonder about the option of choice in selecting one’s path of training for his/her professional career. Thus, while education provides a means for transformation of the child into a worker, the system in and of itself is also under ongoing transformation.

One point of discussion that was of particular comparative interest to many in our group was the role that parents play in the daily operation of the school. Parent organizations have an official representative role that informs school policy. Contrary to common practice in the United States, Cuban parents appear to be more actively engaged in their involvement with the schools in authentic and ongoing ways as they are held accountable by other parents and the students for their regular participation in school activities. We did note that in both the Cuban and U.S. schools, parent involvement is valued as a key element in the success of each child and a given school.

FUSIL…“In order to understand Cuba today, one must understand its history. Prior to the revolution, infant mortality was high, unemployment was high, citizens did not have free access to education, health care, or sports, prostitution was rampant and people were ready for the revolution…..” This was the message of the Head of the North American Division. This visit, which took us to a beautifully renovated and once opulent home, now serving as the offices of ICAP. His role was to explain a bit more about the history of Cuba and some of the assets that Cuba has including human capital. He welcomed us to Cuba, stressing the need for solidarity between Cuba and the United States. In recognition of “transformations” taking place in Cuba.

ALBA

To develop, to work with, and to keep relationships with North American countries.

“In order to understand Cuba today, one must understand its history. Prior to the revolution it is important to note that infant mortality was high, unemployment was high, citizens did not have free access to education, health care, or sports…..”

We have been a country able and willing to share with those who have less…

Cuba Five

ESTUDIO…All Cubans have access to free education that includes university level or technical training, depending on a student’s performance through grade nine and the needs of the municipality. With study in mind, our final “field trip” of the day took us to a local elementary school where we met with the Assistant Director, Boris. We wandered in and out of first through sixth grade classrooms, each grade differentiated by the color of scarf worn with the uniform. The school grounds were surrounded by a locked, chain-link fence and included a three-story, open air concrete building, an asphalt schoolyard complete with many games (hopscotch, four-square, twister), a “Marti” garden (replicating vegetable plants planted by Jose Marti upon his arrival in Cuba), a large cafeteria, and murals depicting Cuban heroes. Each classroom was named for a national hero and contained study materials related to that specific hero. Uniform in size and overall appearance, these small classrooms had a row of desks for the 20 children each dressed in identical uniforms with color-coded kerchiefs identifying their grade level, a television and a VCR, an alphabet strip, one small bookshelf with a few teaching materials, and a row of blackboards, each with the current date AND the number of years since the revolution written on it. Each child had a composition book on his/her desk and eagerly greeted us with waves, smiles, and some interesting questions, the first which took all of us by surprise…”Are they killing people in the U.S.?” These children obviously watch TV and are influenced by media coverage of events in the U.S. A first grader proudly displayed a patch on his left should indicating “I can read,” as with other children. Not to be outdone, another child was quick to let is know that he too could read but had lost his patch.

When asked about the goals of the school, the Assistant Director emphasized the need for more parent involvement, teaching materials, morality training, and trained teachers. When asked what “transformations” are currently taking place in the schools, Boris noted the recent downsizing of classrooms (from 25 to 20 students), the inclusion of English instruction (Russian was taught until the early 1990’s), the addition of a TV and VCR in every classroom, the increase in teaching Cuban history, and a bank of computers in each school.

At the end of a long day, we appreciated the good food, our fabulous guide, and the shot of a cannon, staged to recreate the warning to Colonial-era Havana inhabinants that the gates to the wall around the city were being closed! We found it hard to believe that we stood in Che’s office while Dr. Manuel Yepe, a pre-eminent Cuban scholar, who regaled us with stories of his own experiences with Che and during the counter-revolution. with a man who served as his Director of Protocol. Referred to as a “walking museum” or “The Professor” Dr. Yepe added much life to Cuban history.

We continue to eat beans and rice (today’s was the best so far), move to the music (some better than others), marvel at the sense of community among the people we’ve met, and, of course, sweat (a the few among us do it so well).

Megan and Alison

Day 3

Day 3: Education and Art at the Community Level, or “You have to have culture to be free” (José Martí)

We began our Sunday morning with a visit to the Casa del Niño y la Niña (House of the Boy and Girl), where we met Maria del Carmen and Rosa Sardiña, the women who run this community-based inner-city project that offers painting, music, dance, foreign languages, computer labs, and other skill development workshops to students after their regular school day. They also support learning for teens and adults. The project in the Cayo Hueso (Key West) neighborhood began some ten years ago with the initiative of concerned community members who felt strongly that their barrio needed a place for kids to play other than on the street. (Yet another grass roots enterprise that we are coming to understand as integral to Cuban life). The local neighborhood group of Cayo Hueso (like the one we met Saturday night, they are referred to as “Committees for the Defense of the Revolution” or CDRs) approached the government about their idea and they were given the space of a former corner grocery and converted it into a little community center. The sparse and homemade toys on the shelves initially seemed sad to me, but throughout the presentation, it became clear to me that these folks give something far beyond the newest learning toy or game to stimulate them and “keep them busy” (as we might say)–they give their attention, love, and full respect.

The idea of respecting the child and following his/her interests, needs, and ideas is key principle of UNICEF’s work. Once UNICEF got wind of the project, they came to provide lots of support and develop strong bonds with the local volunteers who work there. These folks bring their skills, time, energy, and love for children – above and beyond their jobs elsewhere to the project (open every day of the week, morning till night). We met Javier (artist), Julio (historian and transportation guy – see photo of his motorbike), Rolando (cultural promoter) and two young boys of about 15 known as “Nuevo Talento” who performed their national award-winning hip hop song about children’s rights (watch clip here). They have been able to educate over 3,000 youth over the past ten years.

Our next stop was Callejòn de Hamel, an alley jam-packed with murals and a couple of simple shops that represent the Afrocuban culture in Havanna. Women were selling different herbs for healing, as well as reading Tarot cards for curious customers. Eclectic art and sculpture filled the spaces, as well as some of the more curious elements of the African “Catholic” religion Santería. We were treated to a “fashion show” and rumba music that is played every Sunday at noon to passersby free-of-charge.

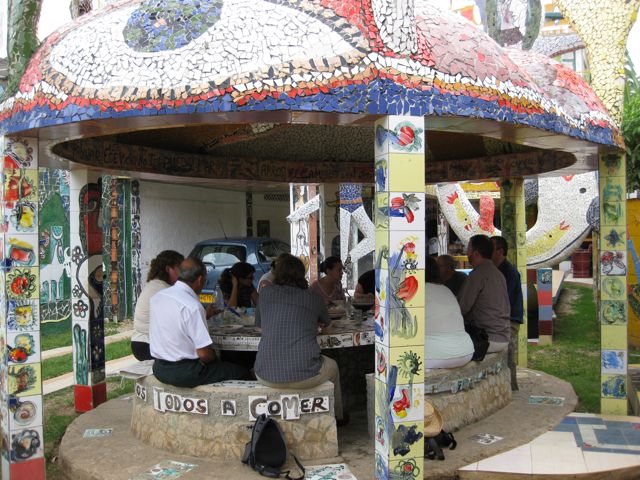

Next, we went to artist José Fuster’s house in the Jaimanita neighborhood. To quote our guide Rita: “it’s a mind-blowing experience.” Fuster’s house and ceramic sculpture garden (think Parc Gaudí in Barcelona) is nestled in the midst of unassuming little one-story bungalows. We sat together with Fuster under a dome-shaped pavillon (made entirely out of his ceramic art), and feasted on rice, beans, fried tuna, carrot, pumpkin and potato salad. The food was fairly typical of what we’ve been treated to in general. It was “good” (i.e. we are not going hungry). We tried hard to think of clever questions to ask (well done Matt), and sweated a lot. Fuster, balding with gray hair, big green glasses, T-shirt, jeans and flip flops, reminded me of Picasso in some ways, and not necessarily because of the obvious presence of Picasso’s style in his work, nor due to Fuster’s reference to Picasso as his “spiritual father”, but rather due to his flirtatious banter with some members of our group (who will remain unnamed).

This artsy early afternoon was a far cry from the sobering visit to the Museum of the Revolution (former Presidential Palace), where we continued to sweat a lot and learn about Castro’s successful expulsion of the Batista government. Dr. Manuel Yepe, former ambassador and assistant to Commander Che Guevara, met us there and led us on a personal tour through the museum. Equally interesting for us was the drama taking place on the sidelines of our visit. Our tour guide, Rita, was spotted by some Canadian students touring the museum, and treated like somewhat of a celebrity. We learned that she had been in a film that the students had seen on women’s rights and sexuality education, so she was a celebrity (and indeed is heavily involved in this work in Cuba).

We finished this exhausting day with an amazing dance lesson on a rooftop, quite literally. No bar, no other patrons, no frills. This couldn’t have been better for our self-conscious little group, who, I might add, did very well learning the Rumba, Cha Cha, Cha, the Son, and Samba with the dance instructor Hester and her five-man band. I can’t write about the actions of the “Wawonko” however – a dance involving “machismo” and sensuality that emerged out of the slums of Havana, but suffice it to say that some (again unnamed, but very sweaty) members of the group did some impressive pelvic thrusts. So ended an eventful day three.

Beth

“Housing is not a place to live, but a place for living” Miguel Coyula, Architect, Group for the Integrated Development of the City.

Our first stop today was to see a scale model of the city of Havana created by the Group for the Integrated Development of the City. Each building and monument in the city has been recreated to a 1/1000 scale out of old cigar boxes (what else?). When we learned of this visit, I thought it was a bit odd, perhaps even quaint. I did not expect that this would be an absolutely fascinating window into the history of Cuban, Cuban urban planning and development, Cuban culture, and more broadly the meaning of community.

If you stand back from the model and squint a little (okay, maybe a lot), it looks almost real, sort of like what you would see from the air. Closer inspection shows perfectly formed little cigar box buildings with no detail or color, other than the color-coding to demonstrate the historical bands of development.

Oddly, there is a similar shifting of perspective when you look at the real city. From afar, if you stand back and squint a lot, there is much grandeur in the city. As our guide to the model, architect Miguel Coyula told us, Cubans like to do things big. The neighborhoods we have walked through are full of grand colonial homes, many with ornate ironwork and glasswork. Each sector of the city contains the remnants and detritus of the dominant power of the time—the grand Spanish villas, the homes of the sugar barons, the elegant hotels and casinos built by the Mafia, and the Soviet style buildings of the 70’s.

A closer look, however, shows that there is a pervasive and nearly universal state of decay in the city. Most of the buildings in our part of the city are literally crumbling.

The house that perhaps best represented the decay for us was the house we came to call the “cat house.” This was a once beautiful Victorian home just two blocks from our hotel that looked to be abandoned by human and left to the cats. There were literally dozens of feral cats on the porch in the windows, and in the yard of the house. The structure itself looked to be totally inhabitable—broken or missing, windows and a crumbling foundation.

We learned today that housing is one of the central problems facing Cuba today (that and transportation). 90% of the people in Havana are homeowners, and homelessness is not permitted. There are no people living on sidewalk grates or on park benches. After the revolution, rents were cut by 50% and the rent payments were immediately applied to ownership of the property. But the cost of repair and maintenance is far beyond the means of nearly all homeowners. Building materials are outrageously expensive in Cuba, and most certainly out of reach for the average person. According to our guide, even a gallon of paint is unaffordable.

As a result, people stay in their homes until the homes are no longer fit to be occupied. There are presently 12,000 people living in shelters in the city. But there are 120,000 people waiting for a space in a shelter, currently living in what here would be considered condemned buildings—this is about, we think, 10% of the city. Buildings in Havana have a very high vacancy rate—we see at night huge concrete Soviet “Bloc” type apartment buildings with very few lights in the window.

These problems with housing are at the forefront of Cuban policy agendas right now, and demonstrate a very interesting type of grassroots urban planning underway. This brings us back to the scale model of the city. The point of the model is to allow policy makers, interest groups, and neighborhood associations to see visually the effects of new development on neighborhoods. Miguel showed us the model of a proposed high rise that some were proposing to be plopped on the coast of the city. A quick mockup of the building placed on the model convinced the decision makers that this was a bad idea—it blocked the view of others and unduly dominated the neighborhood.

Urban planning in Havana is done at the neighborhood level (at least this is the perspective we received from Miguel). His perspective is that “you don’t build buildings that will make people happy, you build to facilitate happiness.” In other words, find out what the people need and want and help make that happen. Build homes that are about living, not simply places to live. Neighborhood groups (much like the Committee for the Defense of the Revolution group we met with this evening) provide ideas of what is important to them and how they want development to happen. The larger working groups gather these ideas and work towards a master plan.

Development is from the neighborhood and for the neighborhood, rather than the sort of gentrification we see here. For example, the section of the city known as “Old Havana” has become a major tourist center since the mid to late 90’s. The tourist dollars that have been coming from sites in the neighborhood have been reinvested into development. The residents are not moved out, but rather their homes are revitalized. With at least one huge development project, one half of a large apartment building offered to house the other half while a portion was being renovated.

Housing very much demonstrates the Marxist “from each according to his ability, to each according to his need” principle (at least in theory). If you own a house, but find that it is not large enough for your family, or that your family is now significantly smaller, you arrange to swap your house with someone else’s. It is a sort of “Craig’s list” of housing. It is not the most efficient of systems–it can sometimes take 2 years to find the appropriate swap.

There is a refreshing blurring of the private and the public that we just don’t see in the U.S.—the public school in the middle of the tourist district, the fanciest hotels are open to anyone to walk through, the restaurant that is also a home, and the neighborhood group that is a political unit. In everything we did today we felt a palpable sense of community and the desire to do what is best for the greater good. We saw it in the vision of urban planning explained to us, in the gay rights rally we participated in (more on that to come), and in the neighborhood gathering arranged for us.

Heather

Day One: Hales Group in Cuba

Our first day of travel was filled with contrasts. Cold, dark, and rainy in Toronto this morning and, just a few hours later, hot, bright and . . . well, okay it was raining in Havana, too. We had some visa issues (that are still in the process of being resolved) that kept us in immigration for 2+ hours, so even more rain was welcomed, as was getting out of the airport and into Havana.

Once we were out of the airport, our bus wound its way through the countryside, past ramshackle stucco, barred windows, banyan trees, fences. Along the way, we were passed by ’48 Plymouths, ’57 Super Chiefs, and so many ’56 Fords, the ancient cars I had read about in National Geographic and Smithsonian. As I watched them come and go, they were off just a bit, not quite right. The closer I looked, the more I recognized that these were not the cars imported to Cuba 50+ years ago. These were something else, something new, adaptations of those familiar fins and fenders. But these were not the only things on the road. Bare with me for a moment longer—there really is a point that is not just about cars.

There were shiny new Volvos and Toyotas, too, and the Russian Ladas, Fiats, Renaults, Volkswagens, Hino trucks, Cuban army jeeps—and lots and lots of buses, filled to the brim with locals and touristas. My ideas of Cuba as an isolated relic of the Cold War had some traction—huge statues, stars and sickles, the faces of Lenin, Marx, Marti, Guevara, Castro. Some of the buildings looked like an East German city just before the wall came down (or so I imagine), but closer inspection showed rundown buildings of varying age and design coexisting and serving so many purposes for which they were clearly not designed. There is the basement apartment across the street from our hotel that clearly used to be a garage. A number of buildings had been built for much more official purposes, with high arches and stucco crests, now apartment buildings. The restaurant where we dined tonight was clearly someone’s living room. There is an ancient fort across the way from beleaguered high-rise hotels that the ‘70s seem to have forgotten.

But, Havana moves; it sings; it flows. It is a city that draws on the entire world, pulls that world into its own unique orbit. It is a city that makes do and makes new. It is a city that, at this point, is so much more than what I had imagined.

Bill Macauley